So You Think the Worst is Now Over?

As of May,15 2021, India has shut down her schools for over 14 months owing to the threatening virus i.e. 2,328 hours’ loss of learning per kid. A recent World Bank’s report estimated that India might lose out on $400 billion in future earnings.

VARUNI

I would like you to think about this: as you are reading through this article, you are living through the greatest crisis India has faced since the Partition of 1947. Distraught victims clinging on to the last drops of oxygen, overloaded hospitals bursting into flames, panicked urban laborers on the highways desperate to get to their homes, these are some of the indelible marks burned into our minds when we think of the pandemic. And, as we are clamoring for better public health infrastructure and social safety nets for the poor, we have another looming crisis yet to unfold in India: future generations foregoing their earning potential due to the sparse, under-efficient schooling and learning mechanisms being provided to them right now. When the schools shut down in March last year, not only have kids stopped learning new things but also, are starting to forget the things they would have learnt. In this article, we shall think about what this “Great School Shutdown” would mean for us in the near future and why that should concern us.

When the schools shut down in March last year, not only have kids stopped learning new things but also, are starting to forget the things they would have learnt.

As a child growing up in the 2000s, I was taught that India’s biggest strength lay in its booming workforce aged between 15 to 64. Economists call this as a “demographic dividend” i.e. when the working age population exceeds the dependent population (children and the elderly), there is bound to be more productivity and growth. Given that 67% of India’s population is of working-age, we would be able to achieve an economic growth much faster than that of US or China but that is based on an important assumption that our young people are adequately educated and skilled: this workforce needs to be equipped with knowledge to drive innovations, fuel research and develop applications to raise our standard of living. From making education a Fundamental Right in 2009 to steadily increasing access to schools and making them as a platform for nutrition and health services, India was making a headway until a lone virus disrupted the progress that has been built over the decades.

Digital Divide is the new inequality

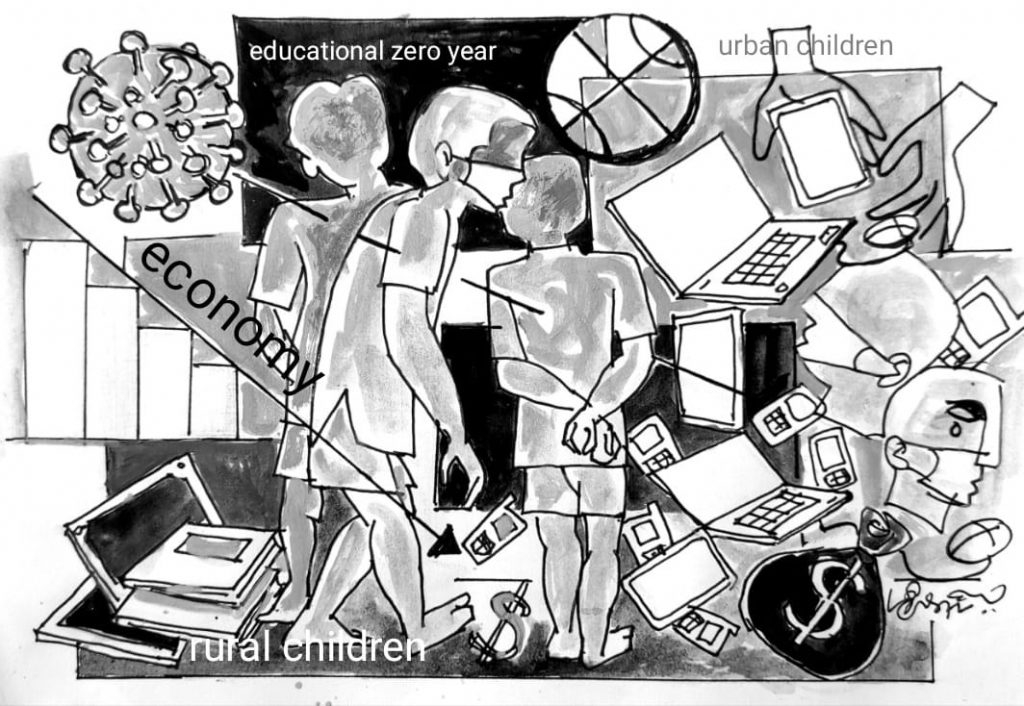

Schools in urban India, especially ones run by the private sectors were quick to transition into the digital education space. This was majorly possible because their students were in a position to embrace digital learning with access to internet-compatible devices. Sadly, public schools run by the government stood at a disadvantage: lack of uniform distribution of digital means among the poor students meant that the public schools could not turn to e-teaching. If the economic divide between students to use digital services was one barrier, another impediment was the urban-rural digital divide: According to the NSSO conducted between July 2017 and June 2018, just 14.9 per cent rural households had access to the internet against 42 per cent households in urban areas.

If the economic divide between students to use digital services was one barrier, another impediment was the urban-rural digital divide:

I think it is fair to assume that readers of this article are relatively well-off, going sheerly by the assumption that this article needs English reading ability, internet, and a device to be able to access it. I could make another assumption that the kids around you are able to access their education digitally and a quick conversation with them about the current state reveals that it is not as efficient and fun compared to the in-person classroom learning. Their counterparts in rural India, especially those from govt schools are worse-off: lack of uniform penetration of internet access to deliver teaching is robbing ordinary citizens of the intellectual resources they might have acquired during childhood. If a poor family were to own a smartphone at all, the head of the household would take it with them when they go out to work and that leaves the kids with just a few hours of access in the evening or early morning.

What steps have been taken to teach kids at this time?

The current desperate times called for innovative measures: India has leveraged its already established DTH services to deliver educational content through TV channels (Interestingly, India pioneered the tele-education model back in the 1960s and by 2004, we became the first country to launch a satellite exclusively dedicated to education). TVs, far more widespread than smartphones, diversified the means to access education remotely and of course, this is assuming that all students have consistent electricity and a working TV/dish connection. State governments like Telangana are utilizing TV channels like DD Yadadri for telecasting regional learning content. Another laudable initiative is T-SAT app which is teeming with high-quality recorded lectures and live-streaming classes for grades 1-10. They have roped in the likes of Neelkantha Bhanu Prakash, the world’s fastest human calculator, to teach kids concepts like trigonometry in Telugu and that is incredibly cool! Similarly, other states would have taken up a few measures.

Key Missing Components

However, the above initiatives have two things lacking in common: firstly, there is a lack of accountability; kids are not answerable to any designated teacher for their work and that naturally allows the human tendency of procrastination to kick in. With their short attention span, kids are bound to get distracted when there is a lack of 1-1 interaction or real time monitoring. This isn’t to undermine the efforts taken up by the Ministries of Education at state and central level but for us to internalize the efficiency of learning being imparted to kids, especially of primary and middle school, in these 2 years of pandemic.

Secondly, notice how the above initiatives ignore the pre-primary school kids’ learning in the digital space? Ages 2-7 form a critical developmental stage for learning. If we were to measure intelligence by the ability to learn and retain new things for longer, children between the ages of 2-7 may be the most intelligent people on this planet. Maybe this is why we are told to utilize the first few years to teach kids as many new languages as possible. To imagine that our country’s youngest (and the most intelligent) age group is being stripped off their learning potential and opportunity for brain development is saddening. Not to mention, the economic inequality which translates into educational gap between rich and poor parents to teach kids at home exacerbates the learning inequality. As an example, my house-help’s extremely smart kid is 6 years old and has lost out on schooling in his 5th and currently, 6th year too. I was told that he could read 1-100 and A-Z and even write 3 letter spellings, but after a few days of revision with him, it was sad to see him struggle to recollect numbers even between 20-30. If he were to return to school next year, which class should he join in? The class he left the school out of as he can barely recollect what he was taught, the class he missed joining this year or the class he is supposed to join according to his age next year? This is just one kid out of the millions who will resume formal schooling next year (if all goes right). We need to start framing policy discourses based on such future dilemmas right now so we as a society take a collective, uniform decision when the time comes.

There was debate on whether 2020 should have been considered as a “Zero Academic Year” because digital learning, keeping aside how effective or in-effective it is, had not been launched until the 7th month of the pandemic.

There was debate on whether 2020 should have been considered as a “Zero Academic Year” because digital learning, keeping aside how effective or in-effective it is, had not been launched until the 7th month of the pandemic. This could have been helpful for kids in the public school who have not been exposed to as much of learning as their peers in private school in the same year, but various ministries have rejected this idea. A few years down the lane, we could notice private school kids enrolling in university at a relatively younger age than their public school counterparts because the former’s education was not disrupted owing to lack of internet. A policy decision that could have ensured level-playing field to an extent but shunned due to the powerful lobbying of private schools who needed to collect fees for the year.

Huge costs ahead

Keeping the inherent social and economic inequities along with school closure in mind, a recent World bank’s report has said India will lose out on a substantial share of its GDP in the future: 400 billion dollars. The average child in South Asia may lose $4,400 in lifetime earnings once having entered the labor market, equivalent to 5% of total earnings. These loss of earnings are calculated based on the lost skills and knowledge that could’ve been acquired during a child’s crucial growth phase. It could also be the case that the child would spend longer time at school to catch up with their learning loss thereby giving up on a year or two from their lifetime working in the labor market.

We notice socio-economic inequality in some form or the other in our everyday lives, and the pandemic will reinforce these inequities even at a more drastic scale.

Moreover, $4400 is an average figure; if we were to keep the rich kids out of this, the cost on the poor will be driven up even higher. We notice socio-economic inequality in some form or the other in our everyday lives, and the pandemic will reinforce these inequities even at a more drastic scale. An immediate example that is unfolding in front of us now is how the vaccine centers in rural India are being flooded by urban folks because they know how to “work around the app” to book slots for vaccination. We are already seeing efforts taken by the government to reach out to kids’ families that are most vulnerable to dropping out from school, especially adolescents and girls, due to the learning setback and early transition into the substandard labor force opportunities in these 2 years. It won’t be surprising to see child marriages on the rise; the pandemic-induced economic distress will provoke poor families to give their girl child away because they have been long perceived as a burden. It is the entire generation and the policy implementation progress being pushed back.

Light at the End of the Tunnel

Any nation that can out-educate us can out-power us; A paradigm shift in the education sector awaits and the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is a step towards that direction. Nothing will be the same in the post-pandemic era, we will see increased proliferation of digital services and a long-awaited digital education should be made mandatory in public schools or else how can we ensure the employability of kids from public schools? Despite these sober realizations, we cannot afford to be complacent and disillusioned. With a Great Crisis comes Great Opportunities for fundamental reforms. It is important to nudge the government to think about the long- term policies that we would like to see them working towards and this could be done in many forms.

With a Great Crisis comes Great Opportunities for fundamental reforms. It is important to nudge the government to think about the long- term policies that we would like to see them working towards and this could be done in many forms.

Here are some of the ideas that I will leave you with…

• social-media activism AKA writing well-informed tweets to raise awareness and tagging the concerned minister or filing RTI appeals to the concerned government departments about their course of action (the writer is currently in the midst of filing an RTI appeal seeking information from Ministry of Education,Telangana, regarding early childhood education in the pandemic considering there has been no dialogue around it ever)

• Normalize using a percentage of your income (1% or 2% annually) to fund an education or donate the now-pertinent tablets/laptops as gifts to the lesser privileged kids (your house-helps’ kids, children from your local public school, reach out to an NGO etc.)

• Pledging some time every day to teach kid(s) in your neighborhood with appropriate social distance.

• Or if you are busy enough, crowd fund a campaign to hire a tutor for your neighborhood’s lesser privileged kids

• And, the most simple yet effective of all, steer your dining room conversations around such pressing issues, talk about what you as a family or a group of friends can do. When there is enough traction, your elected representatives are bound to take action.

Stay safe and hopeful!

Varuni is a recent Economics undergraduate from The Ohio State University having worked with a few professors from Yale on financial inclusion research projects in Bihar. When not found pondering over the worldly affairs, she dabbles in art, photography and hunting for the perfect aesthetic on instagram.